November 9, 2001

Dayton farm bill proposal introduces issue of production controls

Although they may be late compared to the House, the Senate is now introducing farm bill proposals at the rate of one per week. The latest contender (at column deadline) is called the 2001 Farm Income Recovery Act. It was introduced by Senator Mark Dayton of Minnesota. The Dayton proposal brings the United States Senate face to face with a question that has challenged agricultural policy makers since the adoption of the first farm bill, the Agricultural Adjustment Act of May 12, 1933. That act gave the Secretary of Agriculture broad discretionary authority to raise farmers’ income.

One of the authors of the legislation, George Peek, was appointed to head the Agricultural Adjustment Administration which would carry out the provisions of that first farm bill. Peek’s vision was to aggressively sell surplus agricultural commodities abroad to improve farm income. In addition, he advocated benefit payments to farmers and was opposed to production controls.

On the other hand, the Secretary of Agriculture, Henry Wallace, believed that the situation in agriculture in 1933 required an immediate response. Wallace argued that the best option was to require a reduction in farm production. It was not that Wallace was against exports. In fact, he hoped that a rebound in exports would eventually eliminate the need for production controls. But until that happened, he believed production controls were the best way to quickly reduce surplus production and increase farm commodity prices and farm income.

The two men clashed over which was the best means of improving farmers’ income. Peek resigned in December of that year and production controls became a staple of U.S. farm policy until the adoption of the 1996 Farm bill, dubbed by many as Freedom to Farm. Under the 1996 Farm Bill, farm production controls were rejected in favor of a market-oriented approach that looked to exports and foreign markets to solve the surplus production potential that had challenged U.S. farm policymakers over the years. Since the adoption of Freedom to Farm and the unleashing of agricultural production from previous controls, farm prices have fallen, government payments have exploded, and the pressure is on to replace it a year ahead of schedule.

To date, the House farm bill, Sen. Lugar’s proposal, Sen. Harkin’s proposal, and the USDA Food and Agricultural Policy paper have all shied away of anything close to production controls. With the introduction of Sen. Mark Dayton’s 2001 Farm Income Recovery Act, agricultural policy makers are once again confronted with the conflict between those who advocate aggressive export promotion as the way to reduce growing surpluses and low prices, and those who believe that reducing acreage and thus production is the surest way to increase farm income.

Inventory management programs are dismissed by many, claiming that “if we don’t grow it, our competitors will.” So far that sentiment seems to be more of slogan than a scientific finding. Three universities independently tried to find a connection between set-aside and acreage increases of our competitors. No such connection could be statistically determined. During the last three years we have seen competitors’ acreage increase dramatically despite the elimination of set asides and fence-row-to-fence-row production in this country

Specifically, Dayton’s proposal includes a “Discretionary Inventory Management and Program Cost-Containment” section. In order to reduce potential costs to the government in times of overproduction, the legislation would allow the Secretary of Agriculture to establish a voluntary program that would increase loan rates for producers who voluntarily set aside a percentage of their acreage for conservation. A 5 percent set aside would earn the producer a 2.5 percent increase in the loan rate, 10 percent would earn a 5 percent increase, 15 percent would earn a 7.5 percent increase, and 20 percent would earn a 10 percent increase.

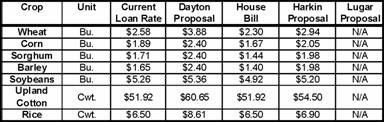

The Farm Income Recovery Act would increase marketing loan rates so that they are not less than 80 percent of the economic cost of production. They would be adjusted annually to allow for changes in producers’ input costs and productivity. Table 1 provides a comparison of the rates included in the Dayton legislation with other current proposals. In all cases Dayton’s legislation provides higher loan rates for producers.

Table 1 Comparison of loan rates contained in Sen. Dayton’s proposal with several other farm bill proposals that are before Congress.

To discourage overproduction, the proposal would establish limits on the crop amounts for which individuals could receive non-recourse marketing loans. It would also prohibit payments to anyone whose annual gross income exceeds $2 million and agriculture accounts for less than 75 percent of that income.

The proposal would also establish commodity reserves to achieve specific policy objectives. The Farmer-Owned Production Loss Reserve would allow producers to store up to 20 percent of their annual production of program commodities. This would be used to supplement the Federal Crop Insurance Program by providing additional risk protection to producers who suffer production losses.

The Humanitarian Food Reserve would allow the government to purchase, store, and utilize commodities to ensure the capacity of the U.S. to fulfill current and future humanitarian nutrition assistance commitments. The reserve would be limited to approximately one-year’s estimated commitments. Programs that may benefit from this reserve are Food for Peace Program, U.N. World Food Programs, and a Food for Education like the one proposed by former Senators George McGovern, and Bob Dole.

The Renewable Energy Reserve would allow the government to store up to one-year’s usage of commodities that are used as feedstock supplies for renewable fuels. These would be used when stocks were low or prices threatened to shut down renewable fuel industries.

Daryll E. Ray holds the Blasingame Chair of Excellence in Agricultural Policy, Institute of Agriculture, University of Tennessee, and is the Director of the UT's Agricultural Policy Analysis Center. (865) 974-7407; Fax: (865) 974-7298; dray@utk.edu; http://www.agpolicy.org.

Reproduction Permission Granted with:

1) Full attribution to Daryll E. Ray and the Agricultural Policy Analysis Center, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN;

2) An email sent to hdschaffer@utk.edu indicating how often you intend on running Dr. Ray's column and your total circulation. Also, please send one copy of the first issue with Dr. Ray's column in it to Harwood Schaffer, Agricultural Policy Analysis Center, 310 Morgan Hall, Knoxville, TN 37996-4500.